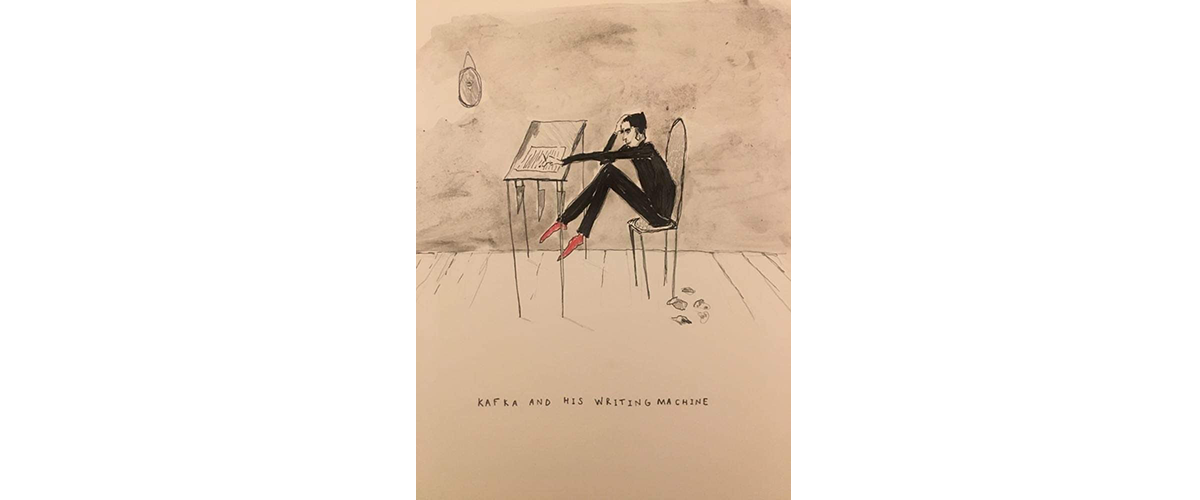

Frances Tanzer, Kafka and his writing machine, 2021.

Historians define time as the progression of events from the past to the present into the future. Time can be measured, explained by a series of events. Historian Nitzan Lebovic is studying a collection of 20th-century German Jewish intellectuals who wrestled continually with concepts of time and temporality. His work reveals that they often viewed time—not space—as the key to their individual and collective experience, rejecting definitions of oneself based on borders, territory or geographic/national origin.

In his latest book project, Lebovic studies the philosopher of religion Martin Buber, critical theorist Walter Benjamin, political scientist Hannah Arendt and poet Paul Celan. The four stand at the center of our contemporary understanding of religion, critical theory, politics and literature. Lebovic, professor of history, examines how they perceived big historical changes and movements. They believed they needed temporal concepts as the core of new disciplines, and a new vision of the 20th century was really at the heart of it, he says.

“Such intellectuals, experiencing the rise of Fascism and Nazism, viewed the 20th century as a time of acceleration, mobilization, innovation and fascination with everything new. Modernity turned its back on the past, even when the cost was deadly.”

The thinkers he follows, then, believed that we need to reconsider time as a key to modern development. It’s not by coincidence that the Germans invented blitzkrieg or that Einstein and Freud reimagined the individual psyche and the universe.

“That’s also where our post-1945 notion of globalism and global culture came from,” Lebovic says. “Within the humanities, that’s how we came to see religion studies, critical studies, political science and literature in general. Temporal concepts were very popular in the second half of the 20th century.”

Modern Jews stood at the crosspoint between two periods: 19th-century liberalism and modern nationalism. On the one hand, liberals demanded to emancipate the Jews as citizens of various European countries. On the other hand, we see the rise of anti-Semitism. The competing ideologies show two different utopian visions, one of a multicultural liberal society and another of pure Aryan race. Neither one considered the formal borders of Germany, between Poland and France, relevant to their vision.

Lebovic’s message is not without hope: “Time is the best equalizer,” he says. “We’re all born, live and die. If you think about that point, your whole identity’s seen with very different eyes because there’s no major difference between someone speaking French and someone speaking German. The thinkers I’m interested in designed their thinking about politics, history, religion and literature from that perspective. It’s how we construct our story—beginning, middle and end—that allows us to think as equal human beings rather than through spatial differentiation, which is always thinking through hierarchies, minorities, those who belong and those who don’t.”