Olivia Landry’s third book asks what documentary film can do to unsettle colonialist conceptions of the colonized.

In the academic discipline of postcolonialism, the concept of the “colonial gaze” attempts to explain the relationship between the European colonial powers of the 19th and early 20th century and the people of the countries they colonized.

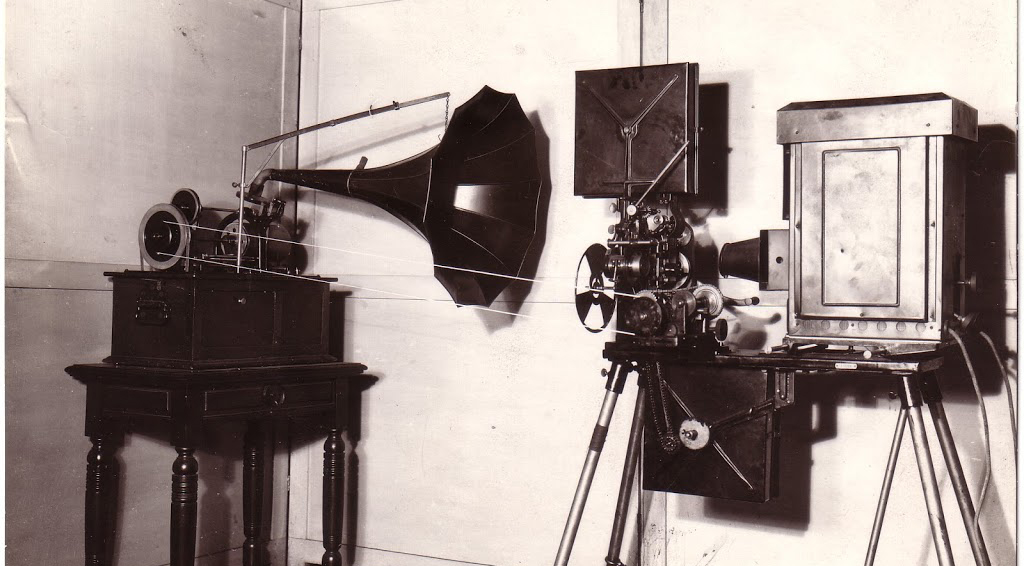

Specifically, it refers to how the colonized were represented in visual media such as photography and film. The idea is that the colonial gaze placed the colonized in a position of the “backwards other” that helped maintain the colonizer’s identity as the powerful conqueror and civilizer, and served as a justification of colonial rule. Olivia Landry, assistant professor of German in the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, has been researching what she calls the “colonial ear,” which, similar to the colonial gaze, explores how the colonized were represented by the colonizers in audio recordings.

“It's easy to think about the relationship between colonialism and photography, and even early cinema,” says Landry, who is also director of the film studies program. “But we rarely think about colonialism in relation to listening, because we have this idea that listening is a kind of gesture of openness and empathy.”

Landry’s upcoming book, A Decolonizing Ear: Documentary Film, the Empire, and the Sound Archive, is the culmination of her research at The Free University of Berlin last summer. Her monograph begins with the ethnographic context in which phonographic recordings of captured foreigners held in German prisoner-of-war camps were collected by the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission between 1915 and 1918.

Many of the prisoners heard on the recordings are colonial soldiers from the African continent and the Indian subcontinent, who were coerced into war by their colonial rulers, France, England, and Russia. Captured colonial soldiers were frequently interned together and subject to additional military and ideological strategies in an effort to turn them against their former armies.

While this effort ultimately failed, the detained prisoners of war became objects of various scientific research projects, including the one carried out by the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission. The ostensible aim of the commission was to systematically record the different languages and music of all those interned in the camps, and it included more than 50 scientists from the fields of linguistics, musicology and anthropology.

“I'm using this specific project as a paradigmatic example of colonial listening,” Landry says. “But ultimately, I wanted to think about how sound might become decolonized through documentary film.”

Of particular interest to Landry is the way in which ethnographic sound recordings are remediated in various documentaries, and how this process of remediation offers a method of what she describes as “decolonizing the ear.” In media studies, remediation is a general framework for considering how media is continually changing, and all media constantly borrow from and refashion other media.

Landry’s starting point for her book was a 2007 documentary film called The Halfmoon Files: A Ghost Story by Philip Scheffner, which examined the audio recordings in the Berlin Sound Archive. The film is Scheffner’s own audio-visual research project on the entanglements of politics, colonialism, and media technology.

“This is an experimental documentary that goes back and listens to a lot of the recordings and spends time analyzing and scrutinizing them,” Landry said. “It also attempts to discover the identity and the history of a number of colonial prisoners whose voices were recorded and part of this part of this project.”

For Landry, Scheffner’s film and an array of others are examples of the nexus of history and media, where materials of the past come alive in the present through remediation, as new media revisit the old. Landry believes that this process forces us to recognize all of the layers of misrepresentation that were in place when the recording occurred, so that we can at least begin to try and get a clearer, more authentic picture of the subjects as they were in themselves.

“The act of remediating sound recordings in documentary film can serve to unsettle their original meaning and intentions,” Landry says. “By placing these materials within a new context, we might begin to listen to these recordings differently. This becomes part of a decolonizing process of unlearning.”

by Steve Neumann